How to reconcile energy independence and decarbonization goals: key challenges and possible solutions

Natalia Collado Van-Baumberghen, Jorge Galindo, Manuel Hidalgo Pérez

8 Jun, 2022

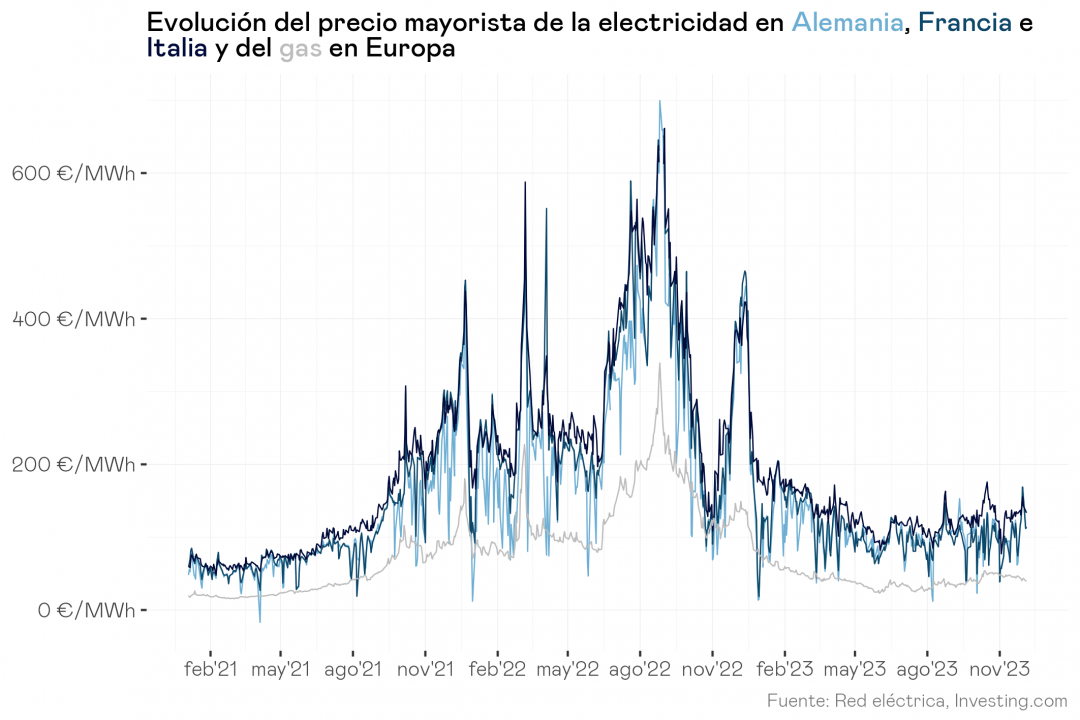

The new goal of ending EU reliance on Russian energy is in addition to and must be reconciled with the existing goal of decarbonising the Spanish economy. This reconciliation seems obvious in the very long term, but in the short and medium terms, it poses challenges for Spain and other countries:

- The immediate upward pressure on inflation, accentuated by disconnecting from Russia, may lead (and is leading) to decisions that encourage emissions.

- The costs of the transition, like those of the immediate pressures, are considerable and not distributed symmetrically amongst the population: they tend to affect the most vulnerable socio-economic groups.

- The mechanisms and decisions necessary to implement an energy mix that can ensure decarbonisation and self-sufficiency are not integrated well enough into either the new circumstances or the differential and asymmetrical costs that may arise, particularly in the very long term (from the next decade onwards) and at the territorial level.

To tackle these challenges, we suggest the following lines of action:

→ Avoid using price caps and subsidies in order to maintain the signal that the prices of products that cause pollution and make us rely on other countries (fossil fuels) are a reflection of these issues, and leave the control of inflation in the hands of central banks as far as possible.

This should make us evaluate the cost of indexing massive transfers, such as linking pensions to the consumer prices index (CPI), this being a measure that encourages price caps and subsidies.

→ Improve the design of the electricity market to ensure that it offers a combination of incentives for the shift towards non-polluting energies, safeguards for the most vulnerable, and increased energy self-sufficiency.

– The ‘Iberian exception’ designed and agreed upon by the Spanish and Portuguese governments could work in this respect, but only if the final price after capping gas prices is sufficiently high to continue encouraging the transition. Price changes after implementation must be monitored closely.

– Another option would be to use windfall profits to fund direct transfers to the citizens affected. This would respect the price signal and sidestep the risk of ceasing to incentivise the transition. However, since this might entail certain legal uncertainties, the possibility of transfers similarly funded by tax should also be contemplated, or other mechanisms.

→ Reduce asymmetrical impact by making compensatory payments to the most vulnerable sectors of society. Before increasing such payments or implementing new schemes, however, steps must be taken to ensure and broaden access to them and make them effective for households in the lowest half or third of income brackets.

→ Give demand more clout by creating a European gas-buying cartel in addition to other measures (tariffs or disconnection from Russia) to maintain greater downward pressure on prices. The respective savings (or part of them) could be invested in renewables.

→ Define a realistic, fair energy mix that retains renewables together with the possibility of exploiting synergies between gas and the drive for hydrogen, establishing a gradual shift from the former to the latter, in which Spain has a part to play thanks to its regasification capacity. Spain’s current nuclear policy should also be reassessed in view of what it could contribute to the new goal of energy self-sufficiency.

→ Invest more in rationalizing demand and energy efficiency, particularly by means of well-targeted, progressive taxation, better information available to consumers, and housing refurbishment schemes.

Research Economist en EsadeEcPol. Máster en Economía Industrial y Mercados regulados por la Universidad Carlos III de Madrid

View profile