The European Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism debate: key policy implications and political challenges as viewed from Spain

Pedro Linares Llamas, Jorge Galindo

10 Dec, 2021

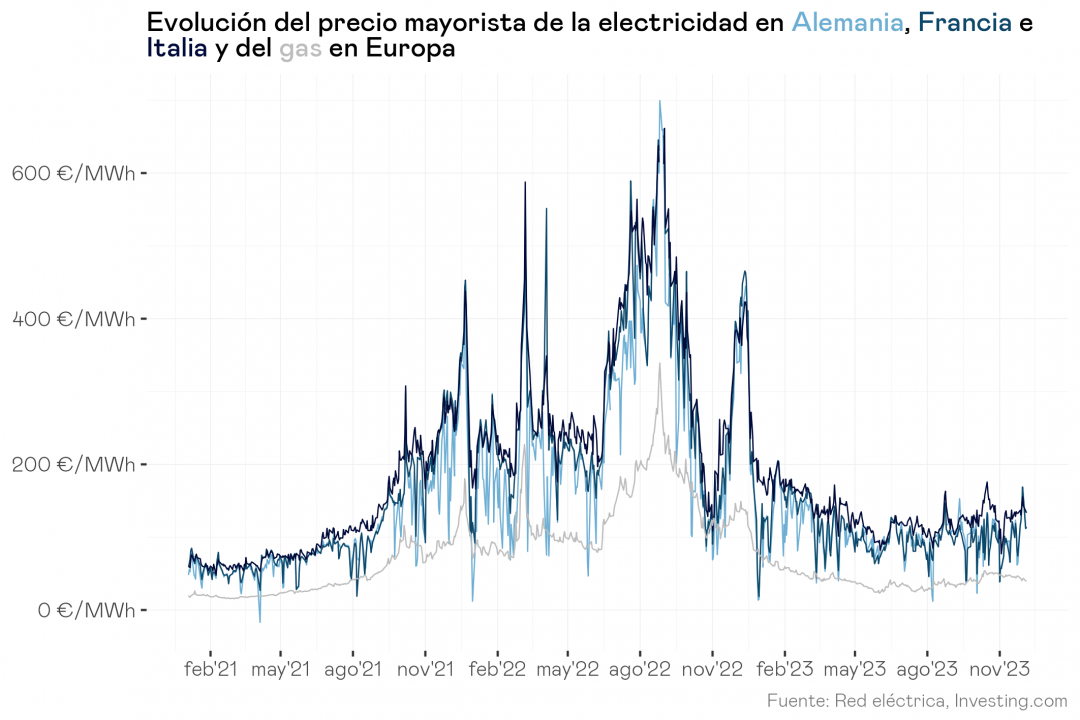

The current system to internalize the cost of negative externalities caused by industries’ CO2 emissions in the European Union is based on a market of emissions allowances that contemplates several exemptions whenever goods are exposed to highemitting, low-price carbon competition. This pricing system is proving to be incomplete: by mitigating (partially or completely) the carbon price through free allowances, it decreases or eliminates the incentive to reduce carbon emissions. Thus, although the price per allowance (corresponding to 1 emitted ton) within the system has been around 30€-35€ in recent years, the effective price in Spain putting together all taxes and mechanisms was estimated by the OECD at less than 15€ in 2015.

To help closing this gap in Spain and around the whole continent, the European Commission proposed last July a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM hereafter) devoted to tax imported products based on their carbon content, hence subjecting them to the same carbon price as European products and reducing the risk of leakage. Sectors initially contemplated are electricity, aluminum, fertilizer, iron and steel products, as well as cement, although the Commission hopes to enlarge the scope in coming years.

However, we foresee four major policy roadblocks to improve the current system through the CBAM proposal, that will undercut is efficacy from the outset.

→ Inapplicability over real emissions. the verification of all the production steps of imported products is nearly impossible. The degree of specificity demanded by the current proposal grants a hard-to-foresee number of loopholes and gives room for tactics aimed at ‘dodging the bullet’ of carbon pricing. This process will be particularly curbersome for trading/commerce SMEs, prominent within the Spanish firm ecosystem. Simultaneously, importers will still be able to use at least two strategies for reducing the apparent emissions embedded in their products:

1. Resource shuffling: certifying as low-emission products those exported to the EU+NAFTA area and leaving the non-certifiable ones for domestic or third-country markets.

2. Sending their products to Europe through indirect routes to benefit from less severe conditions set by other countries. Here, the work of matching to the smallest detail the new CBAM system with existing third-country systems will be crucial. Any asymmetry, which is almost certain to arise due to broader geo-political considerations involved in any negotiation of this caliber, will increase the availability of this strategy. The car industry in Spain is particularly exposed to this and the former risk, given its intricate structure and current reliance on iron and steel imports.

→ Non-verifiable values. A large extent of the values proposed by the Commission when real emissions won’t be verified consist of resorting to default averages (either the average of emissions of the exporting country or, more likely, the average of the 10% top emitters within the EU). Both benchmarks offer plenty of room for non-European producers above both averages, placing virtually no incentive for them to move down. Furthermore, those at or right above the average might be tempted to even raise their current emission level, producing the opposite effect, e.g. the cement sector, quite prominent in Spain.

→ Lack of exemption for exporters. The CBAM proposal does not exempt exporters from paying the carbon price. This cannot be done under WTO rules, since it would be considered an “unfair subsidy”. If cleaner, but less competitive, European products end up being priced out of international markets, carbon leakage is once more a likely outcome, since demand (and thus production) will be bound to shift towards more competitive, albeit less clean, products. Again, metal-based manufacture (e.g. cars, machinery) and cement production might be of particular worry for Spanish interests.

→ Shifts within the value chain. The application of the CBAM to only some basic material sectors may create a shift in imports towards manufactured products incorporating these basic materials while not having to pay the carbon price through resource shuffling or other alternative strategies. These manufactured products typically hold higher value-added. In consequence, an eventual shift would result in a reduction of European income vis a vis the current course, potentially damaging complexly integrated sectors such as car and machinery production.

From a political standpoint, the critical problems to carry on the CBAM implementation fall under two different categories:

→ Inflation effects. Carbon pricing, even when limited in scope, will likely produce a price raise. Inflation related to energy transition is finding a prominent role in import-dependent countries such as Spain. Through these channels, voters are slowly but steadily building a link on their mind between price increases and decarbonization. Any new element with the potential to reinforce this link should be carefully considered from a political standpoint, adding provisions to minimize the potential price impact and balance it out, especially for low-income households that could be disproportionately affected by it. Another alternative would be to pass first the Social Fund, as an umbrella to protect consumers against the negative effects of the CBAM or the ETS extension.

→ Trade & local industry effects. The removal of free allowances pair with the lack of some form of export exemptions could end up expelling comparatively less emitting EU-originated products from global markets. According to current estimates, among the sectors included in the current scope of the CBAM, iron, steel, and cement (precisely those that could have the greatest impact on Spanish production dynamics) account for by far the largest share of free allowances. Other sectors such as ceramics or paper are also concerned for the future) are more affected by this situation.

This implies that the implementation of a policy that runs the risk of producing side effects without significantly achieving its main objective, such as the CBAM in its current design, could serve as a spur to precisely these skeptical perspectives on decarbonization. The coalition that supports them in countries such as Spain brings together small and medium-sized entrepreneurs with semi-skilled workers who could find in this message a point of connection.

It is therefore urgent to put on the table proposals that maximize the desired effect while minimizing the side effects. In that sense, the current CBAM proposal would particularly benefit from extra attention to the differential impacts on the targeted industries, especially the workers who occupy them.

Even more important is to ensure that it much more sharply reduces the risk of carbon leakage throughout the value chain (something that might be better addressed by domestic carbon prices coordinated at the global level). A failed policy of costs without benefits could jeopardize the legitimacy of future policies needed to ensure decarbonization.

Profesor en la Universidad Pontificia Comillas