A review of the government’s emergency measures (and how to improve them)

Jorge Galindo

27 Jun, 2023

Key ideas

→ The use of tax cuts and generalized subsidies was an emergency measure in a situation that demanded rapid responses to curb the escalation of inflation, but it had a limited impact on the households that suffer the most, probably ended up in the pockets that needed it least, has meant an increase in fiscal spending that will be more difficult to remove than it seems, and is damaging incentives to decarbonize.

→ From now on it would be advisable to change the generalized reductions and subsidies for transfers focused on those who really need them, combining them as far as possible in a single channel, with very low entry barriers and clear criteria that prevent capture by those who need them least while they are overlooked by those who really need them.

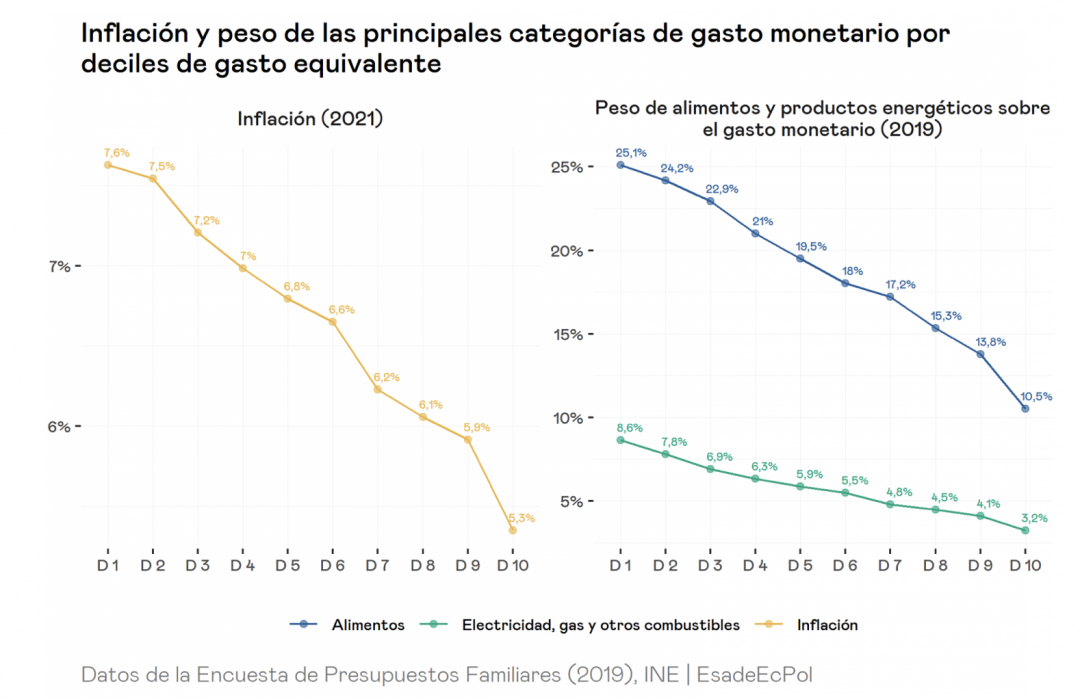

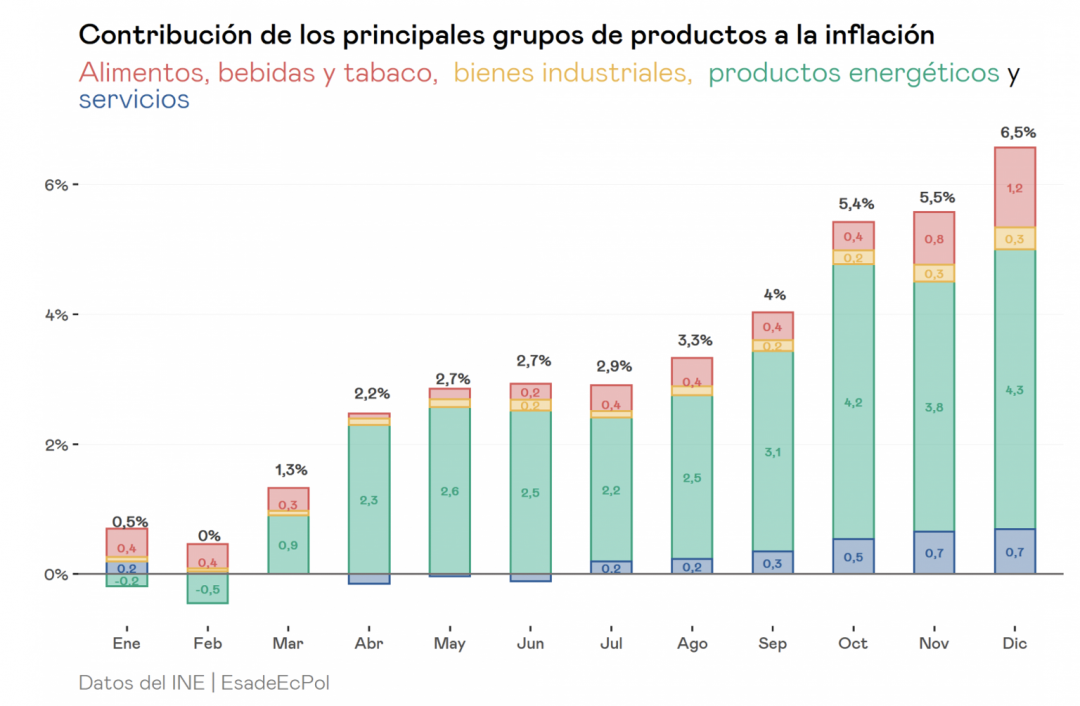

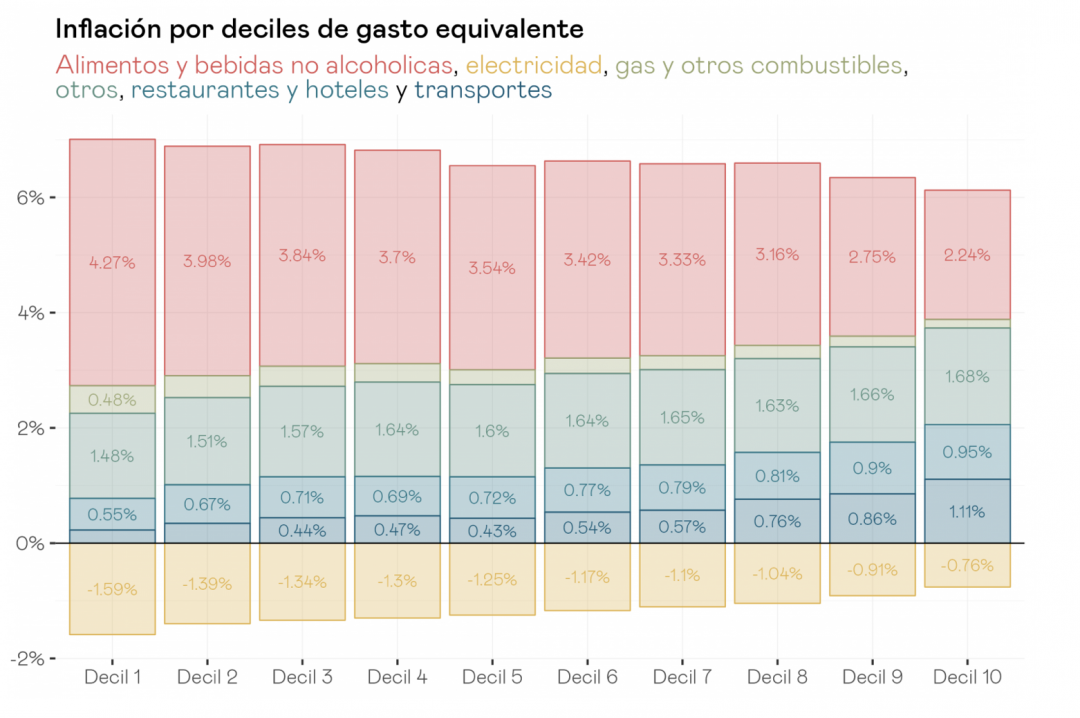

In the midst of the pandemic recovery and facing the crisis generated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the world economies are in an unprecedented situation. Last year’s shock came when economic growth had not fully recovered and inflation was already a reality, which led economies into a state of uncertainty particularly complex to manage, with escalating inflation during 2021 and early 2022 affecting mainly households with lower purchasing power and transmitted especially via energy and food.

In this context, the Spanish government, along with its European neighbors, faced a crucial dilemma: to implement calibrated measures focused on the most vulnerable groups that were receiving this impact, which implied a slower pace, or to adopt faster-acting responses focused on curbing the escalating CPI but less fine-grained (tax cuts, generalized subsidies) and with a considerable fiscal cost. It opted for the second option, which, despite allowing a quick reaction, has resulted in imperfect policies from a distributional point of view as well as from the point of view of effectiveness and efficiency beyond the quick reaction.

Now, more than a year later, these measures are under reconsideration: while the European Commission tells us that it is time to review, the government is sustaining several of them by taking them out of the emergency framework. In this context, and given the new political cycle that will open with the next legislature, it is worth stopping to assess the implications of these extensions based on the work that the EsadeEcPol team has done since the beginning of 2022, considering in light of the evidence whether the effort should not now be directed towards much better designed and targeted measures, which would gain redistributive ambition as well as efficiency, pay a lower cost in terms of damaging incentives for decarbonization, and not further defund our delicate medium- and long-term fiscal situation.

? VAT rebate on food.

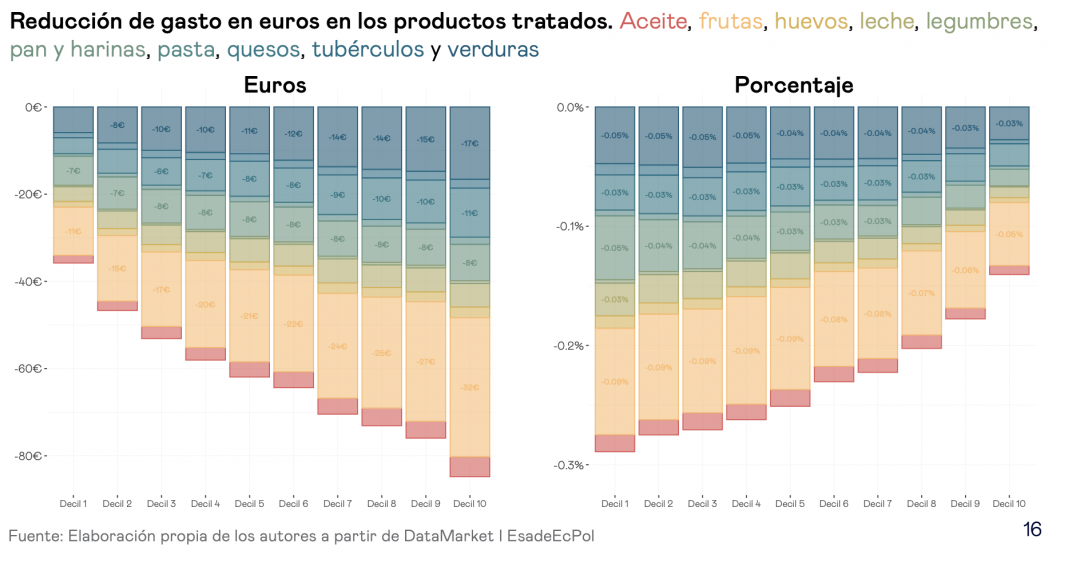

The measure: to cushion the impact of inflation on the prices of the shopping basket, on January 1, 2023 the Spanish government opted to implement a reduction of VAT on staple foods from 4% to 0% (fruits and vegetables, eggs, milk…); and other staple foods (such as raw pasta or oil) went from 10% to 5%. This measure was to be in force for six months, but has been extended.

In this causal analysis we could observe that (at least in large supermarkets, which is where we have reliable data) the rebate was being passed on almost in its entirety to prices, but this did not make it a good measure. The analysis by Almunia, Martínez and Martínez estimated the annual savings at €35 for households in the 10% with the lowest purchasing power and €85 for those in the top 10%. In other words: of the money that the State stopped collecting, more ended up in the pockets of the households that needed it the least.

As a percentage, the estimated savings amount to 0.3% of the total annual expenditure of households in the bottom 10%, and drop to 0.13% for the top 10%: progressive but modest savings percentages compared to total household expenditure, which are just a fraction of the cumulative inflation increase in food: 13% from 2021 to March 2023.

? Discount to urban transport season tickets.

The measure: to reduce the use of private vehicles, the government has been providing free season tickets for Renfe’s Cercanías, Rodalies and Media Distancia services since last year, in addition to offering bonuses on other transport season tickets. Its implementation requires co-financing from the autonomous communities and local councils, which provide additional funding of 20% to 30% provided by the central government. At the end of last year this measure was extended until June 30, 2023, and is now being extended again.

Of all the measures analyzed here, this is the only one that does not directly conflict with the decarbonization objective. However, this is not enough to make it positive. Its effects in encouraging the use of public transport and, especially, in discouraging the use of private transport are still unknown for the Spanish case. In terms of distribution, the INE’s Household Budget Survey indicates that the proportion of the household spent on transport tends to grow with household income, so the risk of regressivity exists. With nuances: there is an upturn in the relative cost of public transport for the poorest. What does seem inevitable is that, as with the VAT reduction on food, most of the money spent will go to pockets with greater purchasing power.

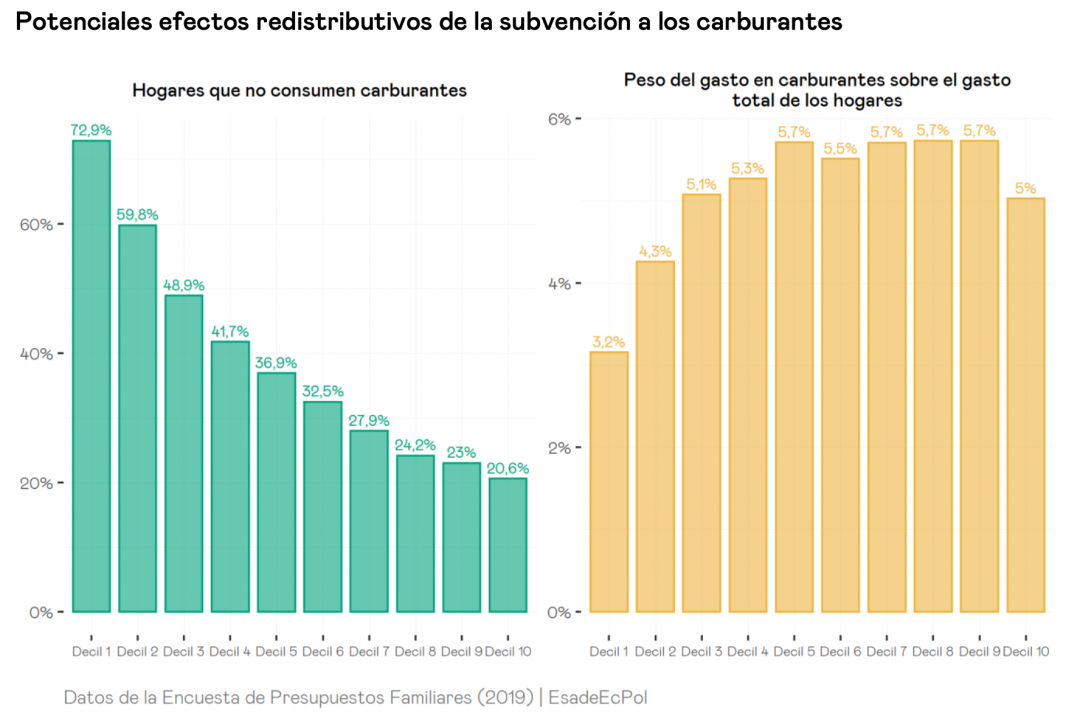

⛽️ Fuel subsidy

The measure: in April 2022 the government implemented a general discount of 20ct per liter of fuel, which from January 1, 2023 would only apply to certain groups of professionals, and which from April this year was only 10ct. In this form it has been extended until September 30, 2023, and a discount of 5ct will be maintained until the end of the year.

In April 2022 we already anticipated that this measure would have regressive effects, benefiting higher income households, which consume a greater amount of fuels. The supervision and punishment mechanisms did not seem to us to be sufficient to ensure compliance with the measure, which would also be difficult and costly for small companies, generating incentives for unintended uses, laterals, or profit capture on the supply side in a sector that is defined by being uncompetitive.

In our subsequent evaluation we would observe that, indeed, although the capture was not large, it was comparatively higher among independent suppliers.

The progressive elimination of this subsidy therefore seems appropriate, albeit slow in its implementation. Along the way we have left almost 6,000 million euros (around 5,700 in 2022 according to Treasury estimates and more than 100 so far this year according to the government) in a regressive policy that damages the price signal we need to sustain to incentivize decarbonization.

? Subsidies and tax rebates for electricity.

The measure: the electricity bonus (discount on the bill) and thermal (single annual payment) are structural aids whose scope was extended in 2022. The electricity social bonus, the most frequent, has gone on to subsidize between 65% of the bill in its default format; increasing up to 80% for severe vulnerable consumers, an expanded version that will be maintained at least until the end of 2023. In addition, the VAT on gas and electricity bills remains reduced to 5% (also for biomass and firewood); furthermore, the rate of the Special Tax on Electricity is 0.5%, the minimum legally allowed.

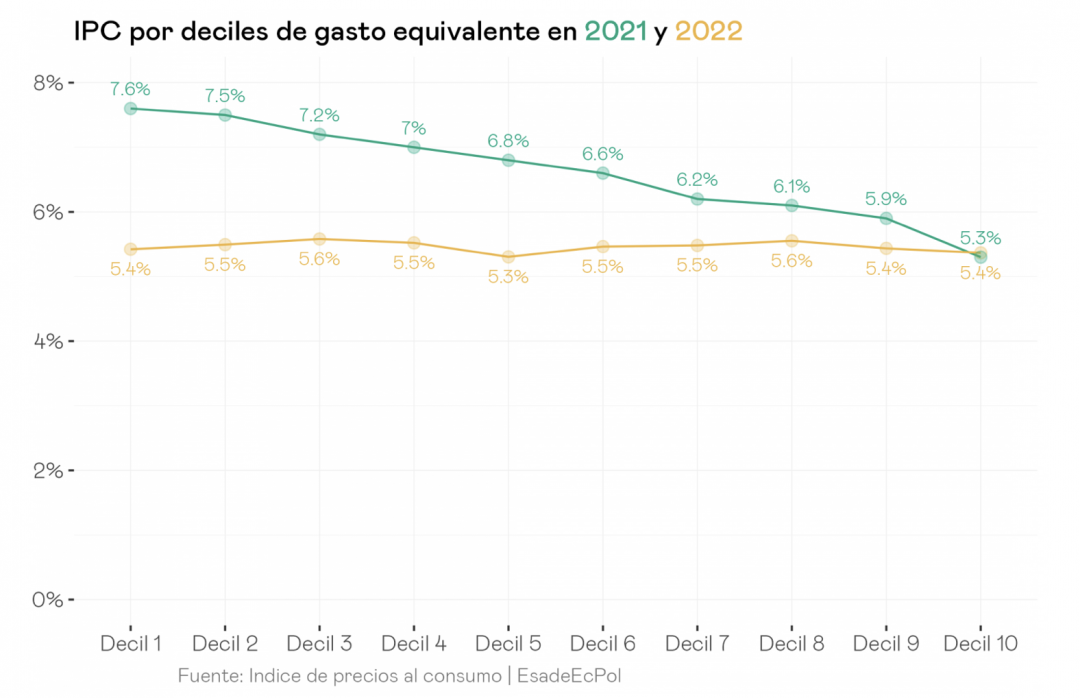

At first glance, inflation in 2022 had a notably less regressive profile than in 2021, and this was mainly due to electricity prices stretching downwards.

But it seems reasonable to presume that most of the credit for this effect belongs neither to the tax cuts nor to the bonuses, but to the compensation to electricity generation through gas: according to our most recent calculations, households with a regulated tariff saved about €209 in the first six months, corresponding with inflation 0.3 points lower for 2022, albeit at the cost of higher gas consumption.

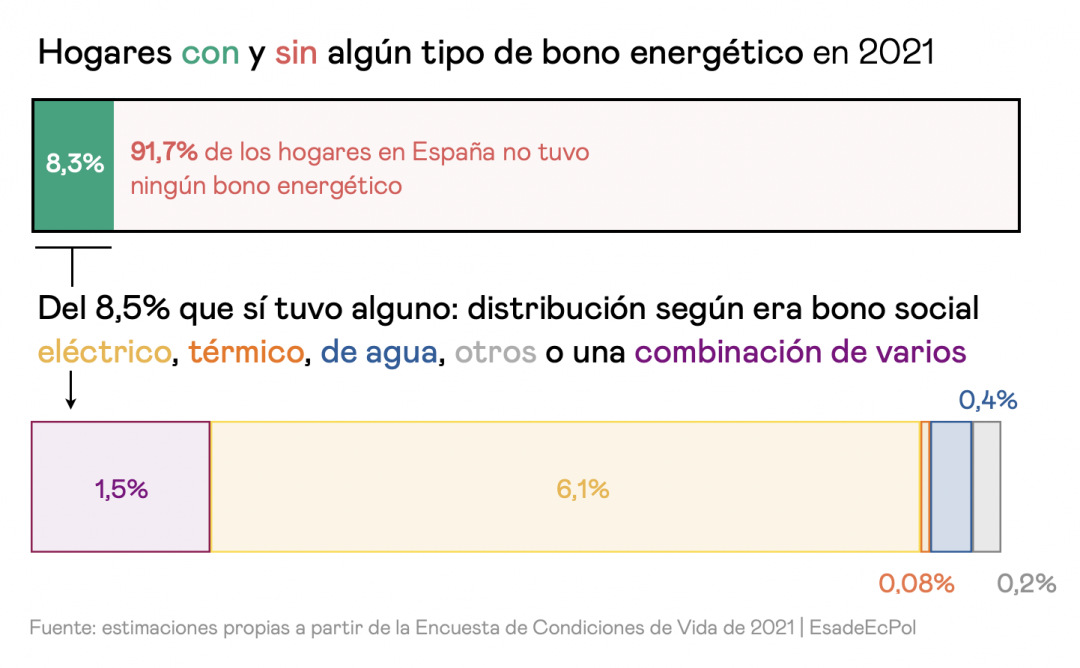

In fact, we calibrate with the Survey of Living Conditions of 2021 that energy bonds only reach 8.3% of households in Spain, although 14.3% stated that they had problems to keep their home at an adequate temperature.

Admittedly, this percentage rises to 17% among the lowest-income third of households, and drops rapidly as we look at middle and upper-middle class households to cover just 1 in 50 families, but it picks up again at the end: 1 in 25 of the top 2% of households in the country has an energy voucher of some kind. And the lowest 10% of income is below the next decile.

With these figures, it seems difficult to see how the vouchers have been decisive for low-income families, and it is worth questioning their basic design: in addition to fragmenting the aid system, turning it into a puzzle that is difficult to understand, the logic of these benefits is still opt-in. That is to say:

Taking the social electricity voucher, for example, it is likely that many households are unaware that they can access this benefit. Even if they are aware of it, they have to be able to apply for it, something that cannot be taken for granted given the complexity of the procedure. This would explain the differential between those who could qualify for it and those who finally do.

*A separate note deserves the IEE, which was originally created to defray the activity of coal mining, and as we said in April 2022 has ceased to have a clear objective, also generating double taxation: VAT is calculated on the total bill plus this tax, so it could be assessed its elimination.

? Alternatives?

The conclusion to be drawn from all the above is that the tax cuts and generalized subsidies implemented in the last 15 months allowed a quick reaction and could have had a certain effect in lowering the escalation of the CPI. But this effect (of variable and debatable depth) came at the cost of three things:

- Blurring of the measures, the total amount of which has probably ended up in greater proportion in the pockets of those who needed it least.

- Increased fiscal spending by puncturing our revenue system to produce dubious effects, and more difficult to withdraw after the fact than it appears once net winners have been created from each new cut or subsidy, as is being seen in the current extension of most measures.

- Damage to the fundamental price signal for decarbonization: if we lower the cost of that energy with associated emissions directly or indirectly, we are doing the opposite of what the evidence recommends to make its consumption more moderate and efficient.

Thus, once we move from the phase of urgent decisions to that of important decisions, the best thing would be to change generalized rebates and subsidies for transfers focused on those who really need them, combining them as far as possible in a single channel, with very low entry barriers and clear criteria that prevent capture by those who need them least while they are overlooked by those who really need them. Making the Minimum Vital Income more robust, inclusive and accessible, or considering the implementation of a complement in the form of a negative income tax, are the avenues to be explored.

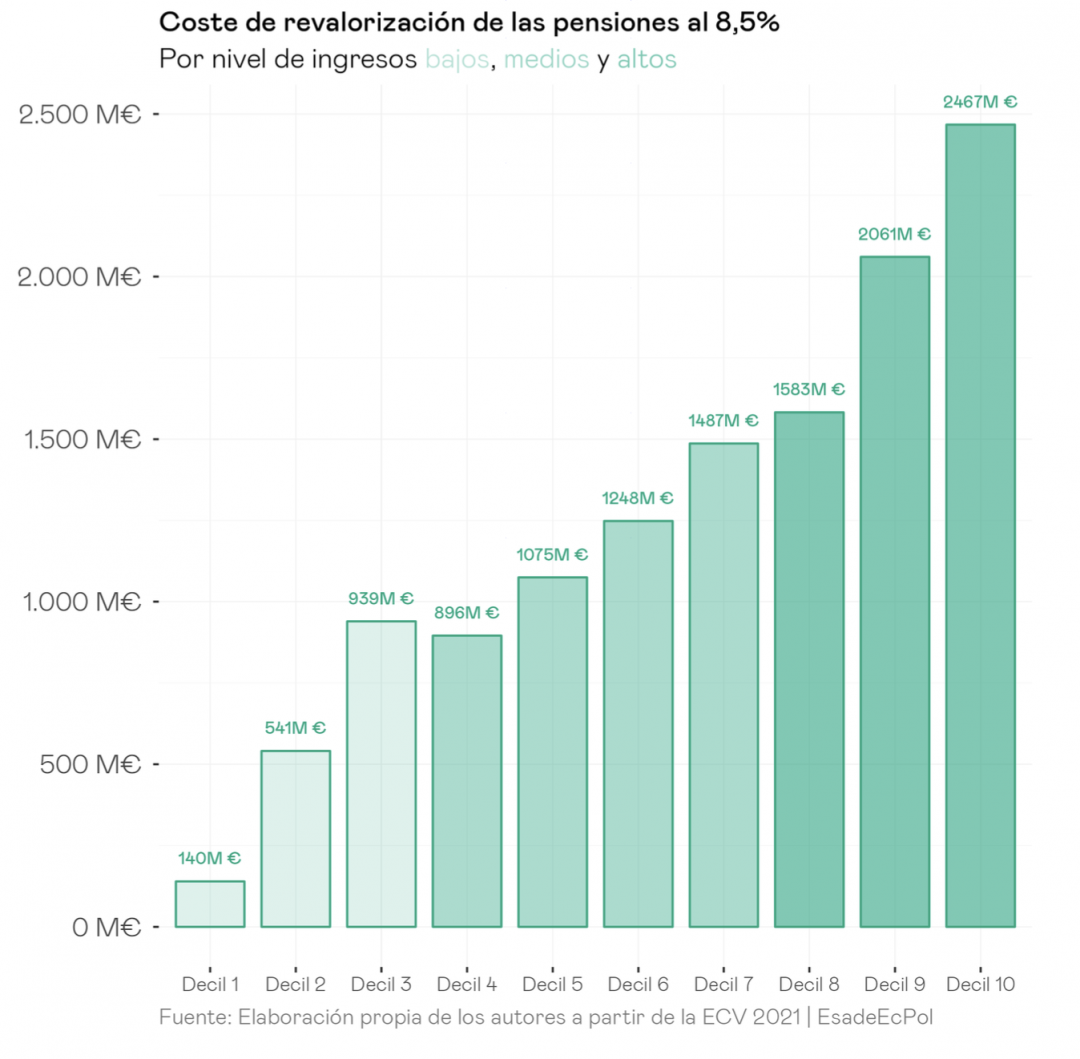

In addition, it would be appropriate to have a more in-depth reflection on one of the most important but less commented reasons for resorting to quick measures: the largest structural expenditure item in the Budget, pensions, is tied to the CPI. An unbridled escalation of the CPI would mean a brutal, unexpected and permanent increase. This was probably a central motivation for several of the measures evaluated here. And, despite this, we ended up with a substantial increase (which has the same problems as described above: more money went to higher-income households).

But pensions do not have to be entirely CPI-linked. Other formulas are possible, and in addition to the obvious advantage of improving the sustainability of the pension system itself, considering them would also encourage slower decision-making in other areas in a world where inflation is once again a problem.